As I discuss with friends about the field of nutrition, and the ways nutrition impacts our well-being positively or negatively, I sometimes hear a conservative feedback about counting calories, especially the practice of fasting. I can bucketize the concerns into two summaries:

- By removing foods are you creating more problems?

- Are fasting and caloric restriction programs an eating disorder?

Fasting is as old as humanity

If you already read the science related to how nutrition can impact health, you know that it’s real, and that there is such a thing as eating to live, and living to eat, in the sense you can eat yourself to sickness over two or three decades. Few things happen overnight, but more happens in 30 years.

Fasting has also been practiced for many centuries, from periods of starvation as well as in many religious traditions. Our DNA is the result of this adaptation as a species over a very long time period. However, the fact that our ancestors starved on occasions doesn’t necessarily mean starving is a good thing. And if there is any benefit, it may help some people and not help others.

Compared to a water fast, intermittent fasting such as skipping a meal and fasting-mimicking diets are more gentle, in the sense that you can eat every day.

Still there is a fair question to ask: can intermittent fasting do harm?

Here is how it can: if you remove certain categories of foods, you risk eliminating macro nutrients (carbs, fats, proteins), fiber, and micro nutrients (vitamins, minerals) which are necessary for life. If the body doesn’t find the nutrients in the bloodstream after you feed yourself, it will start eating itself and possibly get sick from still not getting what it needs. That’s a first problem.

Then, there is a right way to eat (balanced, and adapted to your age, lifestyle, current weight, etc), and a wrong way to eat (binge on junk food, drink too much, put too much salt, etc). There is also a right way to perform fasting, by understanding exactly what you are doing, consulting a doctor first if you have a medical condition or are pregnant, and so on, and there are many terrible ways to fast. For example, you could go on a water fast for days and go for run, or a long bike ride. You could pass out doing this. You could fast for too long, lose considerable muscle mass and weaken your immune system. Or you could fast for not long enough, and get zero benefit, since your body would not have time to clean itself up from within. That cleaning process only happens under very specific conditions, and in other conditions, you get nothing, or worse than nothing.

So, can intermittent fasting hurt you? Absolutely. If we deplete ourselves too much and for too long, eventually the body runs out of nutrients. So when considering a fasting cycle, we need to educate ourselves and do the exercise with a doctor or nutritionist.

Successful intermittent fasting requires eating order and precision

Now that we covered things that can go wrong, and why intermittent fasting can be a disorder, let’s look at scientific experiments and their results. In The Longevity Diet, Dr Longo indicates that in order to be successful with a fast-mimicking diet, you have to be rigorous, understand what you are doing, and do the program in your own context. How old are you? Are you underweight, in the right BMI range, or overweight? Do you have a medical condition? Are you taking drugs? The list of questions goes on. Step #1 is to educate yourself on human physiology, macro-nutrients, and how the body works. Then consider your situation. Read Longo’s book in its entirety, or whichever low-calorie or nutrition program you find scientifically convincing. Consult your doctor, and do the program together with him or her.

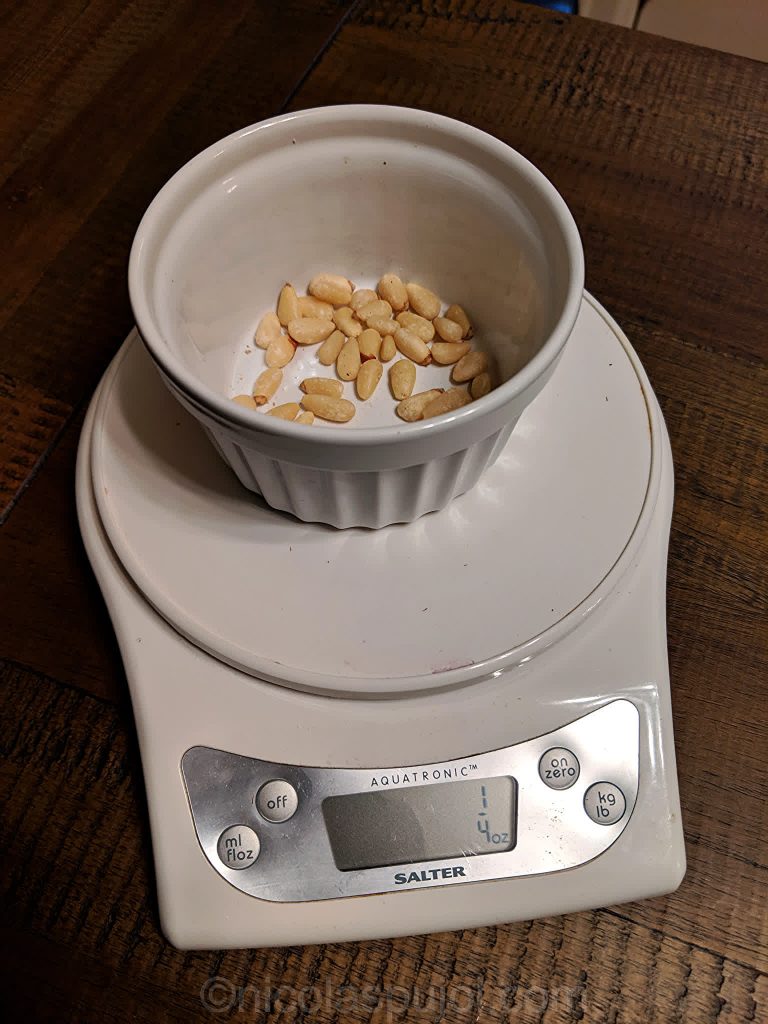

If the goal is to eat a total of 800 calories on a particular day, coming from 50% complex carbohydrates and 50% good fats, you will need to pick ingredients, weigh them on a scale, and add up the total carbs and fats so that you are as close as possible to the target. I don’t think anything can be 100% accurate, but it should be directionally pretty close.

The work from Longo and other researchers emphasizes on doing no harm, so they encourage the use of vitamin supplement and omega-3’s during that week, to be sure you are not missing anything essential. My experience eating fewer calories for 5 days is that it required discipline and some thinking. It required the opposite of disorder. You are introducing variations and perturbations to your regular eating habits, so from the outside it may look like “disorder”, but the scientists ran their experiments that they could define the bounds of efficacy, and by sticking to these bounds, you get the better chances of obtaining results from their study.

FMD, like any fasting regimen, must be considered a learning exercise prior to starting the program, so you know what you are doing, and be performed with lab-like precision. If it’s 100 g of X, it’s not 200 g. And it is X, not Y. So if someone makes fun of you when they see you weigh your kale or your mango, be proud of doing it, because until you know the caloric content of the ingredients you are using, this is the way to do it.

Conclusion on low-calorie “programs”

My experience with low-calorie days or weeks has been OK, and in the case of fasting-mimicking diet I was still eating 3 meals a day. I am not sure I gained or lost anything. My weight was stable, and I did not do it with the purpose of losing weight. Rather, I did it after weeks where I felt I ate too much, like after the Christmas holidays. And back to observing centenarians, I haven’t seen many of them doing “programs”. Rather, they tend to avoid over-eating, excesses, deficiencies, and choose a balanced diet that’s rich in plant foods. Perhaps if we do this, there would be no need to feel like eating less for a week.

Leave a Reply